Artist Interview: Ramsey Nasser

August 30, 2017, 00:00

An interview with Ramsey Nasser on current projects and work he did during his residency

Ramsey Nasser is an Eyebeam alum who was in residence from 2012 - 2017.

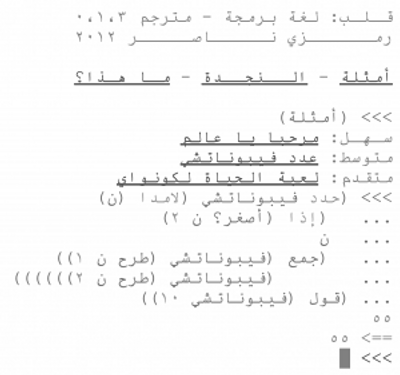

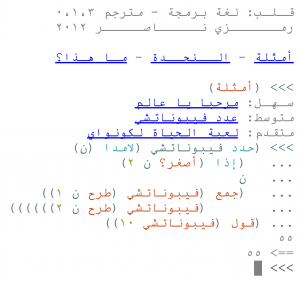

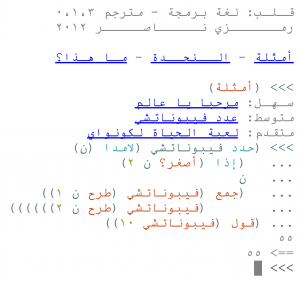

He believes the term ‘digital colonialism’ refers to the imperialistic tendencies of the Western world in today’s digital culture. The work of Eyebeam alum Ramsey Nasser seeks to critique and combat these imperialist tendencies, and his main project while a resident at Eyebeam was the creation of قلب, which is a programming language based entirely in Arabic.

His work also includes a first-person shooter game developed in collaboration with Jane Friedhoff, Handväska!, in which a player smashes fascists with a purse, and in Dialogue 3-D, the gamer is prompted to answer questions about the ethics of violence against Nazis. Eyebeam was able to speak with artist Nasser about his work since Eyebeam, and ways in which he is still involved with us today.

Eyebeam: During your residency at Eyebeam, your work largely focused on the manipulation of traditional assumptions about technology and coding, as with the game Swordfight and the Arabic programming language قلب. What do you typically seek to do when creating? Ramsey Nasser: I enjoy putting people in situations they’ve never been in before, and subverting an audience's sense of familiarity to challenge their assumptions about the world. Swordfight use the familiar Atari joystick in a totally weird way and invites players to interact with others in a manner socially impossible outside of a friendly, consenting game. قلب took the familiar interaction of writing code and changes a single thing about the experience, the alphabet in use. This simple change, of course, changes everything and highlights the importance of the surprising human languages in computer programming.Ramsey Nasser, قلب, programming language developed during his fellowship at Eyebeam, 2013. Eyebeam: Similarly, humor and playfulness are not attributes typically associated with coding or technology in general, yet your work is full of both. What do you make of this association?

RN: It’s always been in my nature to be curious, seek things that make me laugh. I’ve never been an overly serious person and that manifests in my work, I suppose. Anything else would be dishonest. It has also been an effective way to approach difficult topics, like imperialist tendencies in digital culture, without coming off as overly confrontational or self-victimizing.

Eyebeam: Considering your recent pieces like Handvaska! and Dialogue 3-D, how vital is the political climate to your work, and what incites you to make something political?

RN: My work has always been political, though the realities I am reacting to now are more immediate and apparent. قلب and my work in education are both deeply political arcs of my practice, but it’s harder to point to the ubiquitous linguistic assumptions of modern digital culture or the accessibility gap in tech education than e.g. the rise of fascism in America. The shocking visibility of the current political crisis highlights things, but I don’t feel my work has become more political as a result of it. As an artist, I think reflecting on the reality we find ourselves in is my primary goal. Given that reality is never without people, and groups of people are never without politics, I can’t see myself making work that didn’t have some political bend to it.

Eyebeam: Even though you’ve completed your residency with Eyebeam, you are still working on the Playable Fashion program. Could you briefly explain what the program is and what you would like to see it do in the future?

RN: Playable Fashion is an after school workshop program originally founded by Kaho Abe and Sarah Schoemann, and developed by Kaho and me over the past four years. The workshop has brought the world of electronics, fashion, game design, and programming to high schoolers in underrepresented communities in the five boroughs. By providing a free informal educational outside of the traditional school structure, we’ve reached many youngreators and set them on an exciting career path. Many students went on to become maker community organizers or students at major NYC design programs! We’re so proud of all of them!

We’ve been working to document our program and package it up in a way that teachers, librarians, artists, and anyone else with a passion for education can take it, mod it, and bring it to their community. The program is modular, and we offer nine distinct modules that educators can use on their own or along with other parts of Playable Fashion. We’ve completed write ups and materials for all of our modules thanks to generous grants we won with Eyebeam, and we’ve experimented with integrating our content into a local public high school as well. The future is documentation and public dissemination!

[caption id="attachment_4689" align="aligncenter" width="640"]

Eyebeam: Similarly, humor and playfulness are not attributes typically associated with coding or technology in general, yet your work is full of both. What do you make of this association?

RN: It’s always been in my nature to be curious, seek things that make me laugh. I’ve never been an overly serious person and that manifests in my work, I suppose. Anything else would be dishonest. It has also been an effective way to approach difficult topics, like imperialist tendencies in digital culture, without coming off as overly confrontational or self-victimizing.

Eyebeam: Considering your recent pieces like Handvaska! and Dialogue 3-D, how vital is the political climate to your work, and what incites you to make something political?

RN: My work has always been political, though the realities I am reacting to now are more immediate and apparent. قلب and my work in education are both deeply political arcs of my practice, but it’s harder to point to the ubiquitous linguistic assumptions of modern digital culture or the accessibility gap in tech education than e.g. the rise of fascism in America. The shocking visibility of the current political crisis highlights things, but I don’t feel my work has become more political as a result of it. As an artist, I think reflecting on the reality we find ourselves in is my primary goal. Given that reality is never without people, and groups of people are never without politics, I can’t see myself making work that didn’t have some political bend to it.

Eyebeam: Even though you’ve completed your residency with Eyebeam, you are still working on the Playable Fashion program. Could you briefly explain what the program is and what you would like to see it do in the future?

RN: Playable Fashion is an after school workshop program originally founded by Kaho Abe and Sarah Schoemann, and developed by Kaho and me over the past four years. The workshop has brought the world of electronics, fashion, game design, and programming to high schoolers in underrepresented communities in the five boroughs. By providing a free informal educational outside of the traditional school structure, we’ve reached many youngreators and set them on an exciting career path. Many students went on to become maker community organizers or students at major NYC design programs! We’re so proud of all of them!

We’ve been working to document our program and package it up in a way that teachers, librarians, artists, and anyone else with a passion for education can take it, mod it, and bring it to their community. The program is modular, and we offer nine distinct modules that educators can use on their own or along with other parts of Playable Fashion. We’ve completed write ups and materials for all of our modules thanks to generous grants we won with Eyebeam, and we’ve experimented with integrating our content into a local public high school as well. The future is documentation and public dissemination!

[caption id="attachment_4689" align="aligncenter" width="640"] Students from Playable Fashion share their final results after exploring the cross-over of fashion, technology and gaming.[/caption]

Eyebeam: What have you been working on recently, and what will you be doing going forward?

RN: Getting Playable Fashion documented and published has been a major project, and I am excited to punctuate a major multi-year project.

My research into non-latin text on computers has brought me to interrogating display technologies, and where and how they fail the Arabic language. I maintain https://nopenotarabic.tumblr.com/ to document public failures in the display of the Arabic language, and I have begun a research project to reimagine what a digital data type could have looked like if it descended from the traditions of Arabic calligraphy instead of western moveable type.

I also continue to research more expressive programming experiences by building new tools – a trajectory that has taken me into the deepest depths of computer science I’ve ever experienced. The Arcadia Project and its community is making progress, and all the related technologies I needed to build it seem to set the stage for a radically different approach to creative coding. As with anything, we’ll see where this leads!

Students from Playable Fashion share their final results after exploring the cross-over of fashion, technology and gaming.[/caption]

Eyebeam: What have you been working on recently, and what will you be doing going forward?

RN: Getting Playable Fashion documented and published has been a major project, and I am excited to punctuate a major multi-year project.

My research into non-latin text on computers has brought me to interrogating display technologies, and where and how they fail the Arabic language. I maintain https://nopenotarabic.tumblr.com/ to document public failures in the display of the Arabic language, and I have begun a research project to reimagine what a digital data type could have looked like if it descended from the traditions of Arabic calligraphy instead of western moveable type.

I also continue to research more expressive programming experiences by building new tools – a trajectory that has taken me into the deepest depths of computer science I’ve ever experienced. The Arcadia Project and its community is making progress, and all the related technologies I needed to build it seem to set the stage for a radically different approach to creative coding. As with anything, we’ll see where this leads!

More information about Ramsey Nasser’s work can be found on his website. Article by Communications Intern Colin Lodewick and edited by Leandro Huerto. All photos courtesy of the artist. Header gif: Handväska! by Ramsey Naser, 2016.

Eyebeam: During your residency at Eyebeam, your work largely focused on the manipulation of traditional assumptions about technology and coding, as with the game Swordfight and the Arabic programming language قلب. What do you typically seek to do when creating? Ramsey Nasser: I enjoy putting people in situations they’ve never been in before, and subverting an audience's sense of familiarity to challenge their assumptions about the world. Swordfight use the familiar Atari joystick in a totally weird way and invites players to interact with others in a manner socially impossible outside of a friendly, consenting game. قلب took the familiar interaction of writing code and changes a single thing about the experience, the alphabet in use. This simple change, of course, changes everything and highlights the importance of the surprising human languages in computer programming.Ramsey Nasser, قلب, programming language developed during his fellowship at Eyebeam, 2013.

Eyebeam: Similarly, humor and playfulness are not attributes typically associated with coding or technology in general, yet your work is full of both. What do you make of this association?

RN: It’s always been in my nature to be curious, seek things that make me laugh. I’ve never been an overly serious person and that manifests in my work, I suppose. Anything else would be dishonest. It has also been an effective way to approach difficult topics, like imperialist tendencies in digital culture, without coming off as overly confrontational or self-victimizing.

Eyebeam: Considering your recent pieces like Handvaska! and Dialogue 3-D, how vital is the political climate to your work, and what incites you to make something political?

RN: My work has always been political, though the realities I am reacting to now are more immediate and apparent. قلب and my work in education are both deeply political arcs of my practice, but it’s harder to point to the ubiquitous linguistic assumptions of modern digital culture or the accessibility gap in tech education than e.g. the rise of fascism in America. The shocking visibility of the current political crisis highlights things, but I don’t feel my work has become more political as a result of it. As an artist, I think reflecting on the reality we find ourselves in is my primary goal. Given that reality is never without people, and groups of people are never without politics, I can’t see myself making work that didn’t have some political bend to it.

Eyebeam: Even though you’ve completed your residency with Eyebeam, you are still working on the Playable Fashion program. Could you briefly explain what the program is and what you would like to see it do in the future?

RN: Playable Fashion is an after school workshop program originally founded by Kaho Abe and Sarah Schoemann, and developed by Kaho and me over the past four years. The workshop has brought the world of electronics, fashion, game design, and programming to high schoolers in underrepresented communities in the five boroughs. By providing a free informal educational outside of the traditional school structure, we’ve reached many youngreators and set them on an exciting career path. Many students went on to become maker community organizers or students at major NYC design programs! We’re so proud of all of them!

We’ve been working to document our program and package it up in a way that teachers, librarians, artists, and anyone else with a passion for education can take it, mod it, and bring it to their community. The program is modular, and we offer nine distinct modules that educators can use on their own or along with other parts of Playable Fashion. We’ve completed write ups and materials for all of our modules thanks to generous grants we won with Eyebeam, and we’ve experimented with integrating our content into a local public high school as well. The future is documentation and public dissemination!

[caption id="attachment_4689" align="aligncenter" width="640"]

Eyebeam: Similarly, humor and playfulness are not attributes typically associated with coding or technology in general, yet your work is full of both. What do you make of this association?

RN: It’s always been in my nature to be curious, seek things that make me laugh. I’ve never been an overly serious person and that manifests in my work, I suppose. Anything else would be dishonest. It has also been an effective way to approach difficult topics, like imperialist tendencies in digital culture, without coming off as overly confrontational or self-victimizing.

Eyebeam: Considering your recent pieces like Handvaska! and Dialogue 3-D, how vital is the political climate to your work, and what incites you to make something political?

RN: My work has always been political, though the realities I am reacting to now are more immediate and apparent. قلب and my work in education are both deeply political arcs of my practice, but it’s harder to point to the ubiquitous linguistic assumptions of modern digital culture or the accessibility gap in tech education than e.g. the rise of fascism in America. The shocking visibility of the current political crisis highlights things, but I don’t feel my work has become more political as a result of it. As an artist, I think reflecting on the reality we find ourselves in is my primary goal. Given that reality is never without people, and groups of people are never without politics, I can’t see myself making work that didn’t have some political bend to it.

Eyebeam: Even though you’ve completed your residency with Eyebeam, you are still working on the Playable Fashion program. Could you briefly explain what the program is and what you would like to see it do in the future?

RN: Playable Fashion is an after school workshop program originally founded by Kaho Abe and Sarah Schoemann, and developed by Kaho and me over the past four years. The workshop has brought the world of electronics, fashion, game design, and programming to high schoolers in underrepresented communities in the five boroughs. By providing a free informal educational outside of the traditional school structure, we’ve reached many youngreators and set them on an exciting career path. Many students went on to become maker community organizers or students at major NYC design programs! We’re so proud of all of them!

We’ve been working to document our program and package it up in a way that teachers, librarians, artists, and anyone else with a passion for education can take it, mod it, and bring it to their community. The program is modular, and we offer nine distinct modules that educators can use on their own or along with other parts of Playable Fashion. We’ve completed write ups and materials for all of our modules thanks to generous grants we won with Eyebeam, and we’ve experimented with integrating our content into a local public high school as well. The future is documentation and public dissemination!

[caption id="attachment_4689" align="aligncenter" width="640"] Students from Playable Fashion share their final results after exploring the cross-over of fashion, technology and gaming.[/caption]

Eyebeam: What have you been working on recently, and what will you be doing going forward?

RN: Getting Playable Fashion documented and published has been a major project, and I am excited to punctuate a major multi-year project.

My research into non-latin text on computers has brought me to interrogating display technologies, and where and how they fail the Arabic language. I maintain https://nopenotarabic.tumblr.com/ to document public failures in the display of the Arabic language, and I have begun a research project to reimagine what a digital data type could have looked like if it descended from the traditions of Arabic calligraphy instead of western moveable type.

I also continue to research more expressive programming experiences by building new tools – a trajectory that has taken me into the deepest depths of computer science I’ve ever experienced. The Arcadia Project and its community is making progress, and all the related technologies I needed to build it seem to set the stage for a radically different approach to creative coding. As with anything, we’ll see where this leads!

Students from Playable Fashion share their final results after exploring the cross-over of fashion, technology and gaming.[/caption]

Eyebeam: What have you been working on recently, and what will you be doing going forward?

RN: Getting Playable Fashion documented and published has been a major project, and I am excited to punctuate a major multi-year project.

My research into non-latin text on computers has brought me to interrogating display technologies, and where and how they fail the Arabic language. I maintain https://nopenotarabic.tumblr.com/ to document public failures in the display of the Arabic language, and I have begun a research project to reimagine what a digital data type could have looked like if it descended from the traditions of Arabic calligraphy instead of western moveable type.

I also continue to research more expressive programming experiences by building new tools – a trajectory that has taken me into the deepest depths of computer science I’ve ever experienced. The Arcadia Project and its community is making progress, and all the related technologies I needed to build it seem to set the stage for a radically different approach to creative coding. As with anything, we’ll see where this leads!

More information about Ramsey Nasser’s work can be found on his website. Article by Communications Intern Colin Lodewick and edited by Leandro Huerto. All photos courtesy of the artist. Header gif: Handväska! by Ramsey Naser, 2016.